by Nze Izo Omenigbo

“Anyanwu rie asaa kwuru,

Ala ejiri Edeuli kwado ya”

If the Sun consumes seven and survives,

The Earth will back it with Uli expressions”

—Igbo Mystical Axiom

The Expression of the Sacred in Igbo Culture

The nature of expression (divine/sacred, mundane, mystical, occult and aesthetic) in Igbo culture is captured in many well-known Igbo proverbs. The following three examples are very key in this particular sense, “Onye n’akwa nka na adu ihu: the artist/craft-adept often appears to wear a frown in the process of their work”, “Edeala mara mma bu umeala onye dere ya: the beauty of Edeala sacred expression lies in the calmness of its scribe” and “Ube nkiti nwa nnunu bere n’ohia bu izu mmuo gbaara Dibia: the most simple expression of a bird is wisdom to the Dibia—coming from the spirit world”.

In all three axioms, it can be observed that a certain trait appears to be deep rooted in the traditional Igbo mind, and this is the act of often equating mundane observations with spiritual/phenomenal origins/qualities. To the contemporary mind, of course, this will seem ridiculous. However, in many provable ways, this pattern of understanding has been recognized as a major intellectual catalyst in some of the world’s earliest artistic/scribal traditions and societies.

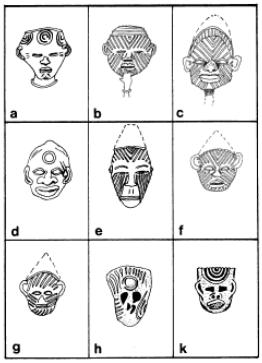

In pre-modern times—contrary to conventional notions—there were at least four existing Igbo scripts, these were Edeala, Uli, Ukara and Nsibiri/Nsibidi. There is no known single origin of the scribal tradition in Igbo culture and most of the available accounts are heavily couched in myths as is the tradition; the better part of which are reserved for the highest initiates. However, some of these mythic narrations (given their heavy roles in the enculturation process of the general society) were often modified by the priests and passed on to the community griots—who later narrated these stories to the young/old of the society.

Also, significant of mention is the existence of many other cult symbol scripts, many of which are yet to be written down or even conventionally known. In a nut shell, it’s a well-accepted fact (at least within honest academic circles) that the scribal tradition has its roots in Africa. Yet often than not, there have also been adverse arguments as to whether such preserved/discovered inscriptions are of direct/literal or symbolic orientations; in other words, if they qualify as “writings” as we understand them today. Needless to say, this approach of judgment is highly biased; since strictly speaking, most ancient societies understood human expression—and expression generally—to be symbolic in its primary nature.

Resolvedly, most of the less esoteric cult teachings of the time were expressed through highly complex symbol systems—from which originated some of the mundane writing traditions of the modern world. Therefore any attempt to understand the communicative modes of ancient societies without an initial, dedicated understanding of their worldview—as concisely shown here—is erroneous by default. In the course of this discourse, insights will be drawn from two of such mythic narrations. As well, few snippets will be equally utilized from one of the aforementioned esoteric myths.

The Principle of the “First Word” in Igbo Cosmology

The archetypal Igbo society held that words were so potent that one must ensure to count their “teeth with their tongue” before or after any question. It is an advice for one to find out something for oneself, especially when one is indulging in self deceit and is seeking for answers from some other person instead of self-reflection. Usually the person advicing will say “i choro ka m gwa gi ya; were ire gi guo eze gi onu–Do you expect me to tell it to you? Count your teeth with your tongue.” However, in dealing with written expressions, the potency inevitably doubles, since the idea being communicated will now (supposedly) outlive its author. There is also the mystical tradition of “the first word” i.e. okwu izizi. In many ways, this ancient principle encapsulates—in totality—the Igbo cosmic orientation of life in relation to the Divine. The mystery of the first word is well illuminated in the classical Igbo tale about the journey that was undertaken by the Dog (Nkita) and the Tortoise (Mbekwu Nwa Aniga).

In this tale, it is held that the Dog and the Tortoise were both sent by humans to deliver two important messages to Chukwu; from which will be determined whether human beings will live to achieve immortality or die at a certain age. To the Dog was given the message of immortality, while the Tortoise was given the message of impermanence. As they both set out for Chukwu’s house, the Dog—priding itself with its ability of swiftness—was said to have stopped several times along the way to sleep, scout for bones or even a mating partner, while the persevering Tortoise continued on its path, undistracted. In the end, the classic endurance of the Tortoise led it to Chukwu’s house, long before the Dog—who was outraced during its many short breaks to sleep or explore the road sides.

Hence, Mbekwu Nwa Aniga (the Tortoise) delivered its message of “Death for the Humans” and thus was the mystery of death introduced into human life. Of course, the Dog did arrive later on—totally convinced that it was the first to reach Chukwu’s house, only to be told that “Chukwu and the Spirit World” does not accept second “Words”. Hence originated the Igbo mystical phrase “okwu izizi erugo be Chukwu: the first word has reached God’s house”.

From this particular tale, a great deal of Igbo cosmological principles dealing with expressions—can be illuminated. Firstly, there is the duality of life as represented by the two choice animals. The principle of duality remains a core aspect of Igbo life and spiritual practices till this very day. And then there is the principle of pre-duality or unified existence. In other words, creation: although dual in nature proceeds from a unified point of One. Hence, the Dog was told that Chukwu and the Spirit World do not accept the second “Word”. The second word here symbolizes physical creation, realized in the sacred number Two.

Also, there is the principle of Uncontrolled Motion/Chaos and Controlled Motion/Order. Both principles were symbolized in the specific choice of animals used in the narration; where the Dog’s undisciplined swiftness stood for chaotic motion and the disciplined fortitude of the Tortoise stood for ordered motion. Both principles were further made potent in their meanings by the messages that both animals were meant to deliver. In the case of the Dog (embodied chaos) the message was immortality (unending spiritual enlightenment), while for the Tortoise (embodied order) the message was impermanence (interrupted spiritual enlightenment).

The Spiritual and Aesthetic Potency of Human Expressions

As the Dog was late to reach Chukwu’s house, it then resulted that human life (as a mortal opportunity for spiritual learning) will be eternally teased with the mystical potency of Ndu Ebi-Ebi (Everlasting Life/Immortality). Just as the delivered message of the Tortoise meant that human beings (indeed all creations) will be forever bound to the physical responsibility of observing/maintaining Divine order.

This dual expression most likely gave rise to such classical Igbo thoughts as “okirikiri k’eji ari ukwu ose: the pepper tree is only climbed by means of cautious encirclement” and “nwayo-nwayo k’eji aracha ofe di oku: a hot soup can only be consumed gently”. Furthermore, the Dog symbolism is equally characteristic of the archetypal Ego (the precarious pride that originated with the Dog’s knowledge of its swift abilities). While the Tortoise in this sense, symbolizes the Super Ego (the self-regulating aspect of us that strives for perfection and orderliness). Although, this last feature is essentially interpretational, the instructional nature of the original tale however supports its validity.

In a sense then, it can be observed that the Igbo worldview fundamentally perceives human expressions/expressions generally as a holistic exercise. Indeed, the greater implication of this conviction is that no expression of creation/life is devoid of meaning and no human expression is devoid of sense; regardless of how “senseless” that expression might seem. This notion is well established by another ancient Igbo principle (stemming from another mythic account) which holds that Chukwu created the world using two words, Ọm and Om.

These two Divine expressions, according to ancient Igbo mystics, became “The Two Sacred Words” i.e. Okwu abuo Chukwu ji were ke uwa”. Again, the basic notion here is duality—but specifically this time; duality dealing with the two Igbo mystical principles of Akwu na Obi (Stillness and Motion). It is remarkable to note that these two principles unified, remains one of the most utilized and infinitely explored of all Igbo mystery teachings. The “Two Sacred Words” as explored in another Igbo mystery cult is also held as the “Two Primordial Sounds”. In this respect, it expresses one of the most esoterically studied of all Divine expressions i.e. sound. In Igbo mystery circles, the naturally produced human-sound (phonetically molded continuously from birth, eventually condensed into a specific lingual form as the child matures) is held to be a mystery of its own. Hence, the ancients explored it in a separate, dedicated cult where its latent creative powers were synthesized for use in invocations, spiritual chants and several forms of oracular practices.

It can therefore be noted that the mystical/occult potencies of human expressions (in a very broad and in-depth sense) have always occupied a place of great significance in Igbo mystery traditions as well as, Igbo culture proper. In this sense, ancient Igbo mystics, after much in-depth observations, were able to ascertain that our voiced expressions do not merely stem from some innate human tendencies to communicate archetypal emotions, as is conventionally held today. But rather, every word we utter and each syllabic expression thereof is actually a released potency. The same goes for aesthetic/artistic expressions; as all forms of human articulations are essentially generated from one point of activity in the mind and charged forth with spiritual potency—at the point of release, whether consciously meant or otherwise.

It is for this great reason that another ancient Igbo axiom maintains that “okwu Igbo/uke bu n’ilu n’ilu: the Igbo language/cult communication is expressed through aphorisms”. Suffice it to say that the ancients well-considered the potency of their expressions/language (indeed the Igbo language in this case) apparently too heavy for any mere direct conveyance of ideas; given the possibility of unanticipated manifestations resulting from careless utterances. Hence, their language/voiced expressions had to be communicated by means of proverbs and indirect insinuations, colored once in a while by plain riddles and chants. Remarkably, this pattern of communication is still observed by the Afa, Mmonwu, Ekpe and Agwu cults (some other Igbo cults inclusive) till today.

It is also interesting to note that even the non-human naming tradition also followed this principle in the past. So that animals, trees, mountains, rivers and other forms of creation were not merely named through direct articulations of their perceivable essences. Rather, it was through a metaphorical intellection of their place in the greater scale of life that their names were articulated. For instance, the Chameleon (in Igbo culture) didn’t get its name from its immediate perceivable characteristic of rapid coloration. Instead, its name “Ogwumagana” literally translates as “If it sinks, I shall not step”. Hence, the name metaphorically denotes the ancient belief among the Igbo that the Chameleon was created at a time when the Earth was still wet. Thus it literally had to enquire from Ala (The Earth Goddess) before making each step, lest it sinks.

Also interesting is the fact that the Chameleon is sacred to Ogwugwu, an Igbo fertility Goddess. The name “Ogwugwu” also denotes a hole or the act of digging. Remarkably, conventional science has been able to determine that matter is basically a hole dug by sub-atomic propellants in space (ether). Therefore, the obvious connection between the Chameleon and this Goddess—as was long established by ancient Igbo mystics—not only preceded modern scientific thought, but unlike the latter, was more clearly expressed and aptly symbolized; so much so that even a youngster could grasp the concept. This tradition, so obeyed, extended even into the designation/articulation of numerical principles, planetary bodies and highly abstract undertakings such as astronomical calibrations.

Furthermore, the aesthetic principle of expression in Igbo culture is also embodied in the aforementioned Uli body-painting/inscribing tradition. The Edeuli or Uli, for short, is a sacred, linear-oriented body-inscribing aesthetic employed by women in pre-contemporary Igbo society. It’s highly attractive and intricately executed expressions were regarded deeply by women and young girls—even beyond the Igbo cultural area. Among other things, it is also a key feature of the Ala (Earth Goddess) cult.

Conclusively, as the name of this discuss states, “Chukwu bu Ulidereuwa: God embodies the Divine Script through which all creation was expressed”. In other words, the expressive nature of Chukwu as the primal aesthetist, as the most accomplished author that will ever be, as the first and original artist of all creative forms that ever was, is and will ever exist—is here underscored. From the ongoing, it is not only made clear that the tradition of expression in Igbo culture is apparently complex in both scope and depth, but also, the inexhaustible nature of indigenous knowledge preserved in Igbo culture is equally made evident here.